Ahmed Koroma's Letters from America - Part 2

Ahmed Koroma’s Letters from America were first published five years ago. This is Part 2 of the six-part series, which ran on July

30th, 2012.

Suba Ranka picked up

his cutlass, wiped the blood with his fingers and smiled. He had killed again.

Only this time, the victim was a goat. He meticulously picked his nose and

looked around. He was getting really good at this; chasing goats and chickens around

the baffa and killing them one after another.

Last night, as he ran around the village looking for goats and chickens,

he realized that the moon had suddenly disappeared. The place had gotten dark

and his victims were hard to find. He had killed the moon, too. He took one more look at the dead goat. I am

going to pluck the wings off the goat before it flies away. He was really good at this. Last night, just

before the moon disappeared, he had sworn that one day he would take a big

knife, climb the court barre wall and take a stab at the moon. He didn't know

why and he didn't care. He knelt down, placed the goat towards the east and

started praying:

"Kuru O, kuru!

Bless this boy, this son of yours. I bring happiness to your face don't you

see?"

He was getting upset as he continued to pray. "I bring you goat meat, can't you see?" He was sweating profusely. Not from chasing the goats and chicken; he wasn't sweating then, he swore. He was sweating from praying. Suba Ranka was rejuvenated by the sudden reappearance of the moon. It was bright again and the constant perturbation of his heart and the sad rhythm it played was gone. He wasn't sweating anymore. He picked up his cutlass and ran for the hills, towards the moon.

He was getting upset as he continued to pray. "I bring you goat meat, can't you see?" He was sweating profusely. Not from chasing the goats and chicken; he wasn't sweating then, he swore. He was sweating from praying. Suba Ranka was rejuvenated by the sudden reappearance of the moon. It was bright again and the constant perturbation of his heart and the sad rhythm it played was gone. He wasn't sweating anymore. He picked up his cutlass and ran for the hills, towards the moon.

Story-telling was part of our growing up in Freetown. We were fascinated with them, particularly the so-called tales of the forest, the Bra Spider and Cunning Rabbit stories.

My favorite story was Good Baba and Bad Baba; the story of a good brother, who performed kind deeds on their journey across town, and his bad brother, who had to pay for his evil ways.

The reason for re-living those days of storytelling in this

letter, the night lamps, and cheap fast food, is not only for nostalgia.

Or the fact that our kids, born and raised in America—and in spite of their electronic gadgets and video games—are missing out on this fundamental rite of passage. But because some of us sometimes fail to appreciate the contribution of these stories, the storytellers, and the impact they made on our lives.

There is something to be said, if you will, of the oral tradition of telling stories and its significance in the broader society.

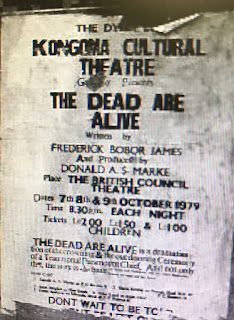

As I look back on growing up in Central Freetown, I think of those halcyon days when we would rush to the then Victoria Park to watch Tabule Experimental Theatre’s improvisation performance at the central bandstand. How easy it was for Dele Charley and his crew to transform ordinary tales into improvised act not only to entertain but to teach. There were folks like Dennis Streeter, Raymond De Souza George, Julius Spencer and Bunting Shaw, to name a few.

Or the fact that our kids, born and raised in America—and in spite of their electronic gadgets and video games—are missing out on this fundamental rite of passage. But because some of us sometimes fail to appreciate the contribution of these stories, the storytellers, and the impact they made on our lives.

There is something to be said, if you will, of the oral tradition of telling stories and its significance in the broader society.

As I look back on growing up in Central Freetown, I think of those halcyon days when we would rush to the then Victoria Park to watch Tabule Experimental Theatre’s improvisation performance at the central bandstand. How easy it was for Dele Charley and his crew to transform ordinary tales into improvised act not only to entertain but to teach. There were folks like Dennis Streeter, Raymond De Souza George, Julius Spencer and Bunting Shaw, to name a few.

Tabule Theatre -- and the then emergent crew, Freetown

Players with Charley Haffner – resonated well with the tradition of

transforming stories into actual performances on stage or on street corners. I

am reminded of those performances every time I walk through the streets of a

major metropolitan city in America, like New York City or Los Angeles.

I owned a copy of Raymond De Souza George’s BORBOH LEF, a spectacular play that was performed at the LIFT festival in the United Kingdom circa 1982, with the assistance of the British Council.

BORBOH LEF, featuring Sorious Samura playing the lead role, was a hit. So were the performances at the Mary Kingsley Auditorium at Fourah Bay College featuring my good friend, Dwight Short, in the leading role.

But how I wish most of the other performances were in still print so we could fall back into them, from far away in distance and time.

I owned a copy of Raymond De Souza George’s BORBOH LEF, a spectacular play that was performed at the LIFT festival in the United Kingdom circa 1982, with the assistance of the British Council.

BORBOH LEF, featuring Sorious Samura playing the lead role, was a hit. So were the performances at the Mary Kingsley Auditorium at Fourah Bay College featuring my good friend, Dwight Short, in the leading role.

But how I wish most of the other performances were in still print so we could fall back into them, from far away in distance and time.

Well, that is until I stumbled upon them at the University

of California, Los Angeles, library when I worked there as a research associate

at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

[There was] Thomas Decker’s JULIOHS SIZA, a Krio translation of William Shakespeare’s JULIUS CEASAR, BAD MAN BETE PAS EMTI OS by Esther Taylor-Pearce, GOD PAS KONSIBUL by Lawrence Quaku Woode, and PETIKOT KOHNA by Dele Charley.

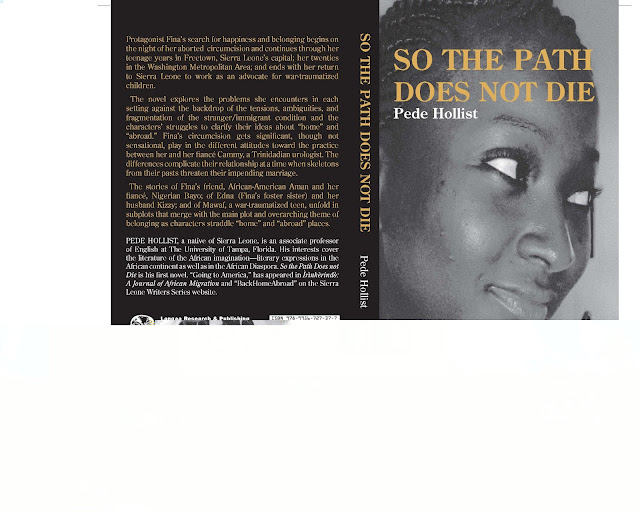

But the big enchilada, the surprise of all surprises, was a book titled THEATER IN SIERRA LEONE: FIVE POPULAR PLAYS, edited by Iyunolu Osagie. The collection included the masterpiece BLOOD OF A STRANGER by Dele Charley, a play that was performed at the FESTAC in Nigeria in 1977.

The other huge surprise was John Kolosa Kargbo’s LET ME DIE ALONE.

Kargbo, a playwright, was arguably, the best to come out of Sierra Leone’s theater world. As a kid, I watched Kolosa plays like POYOTONG WAHALA and EKUNDAYO. He was instrumental, challenging and very detailed. He was a fearless warrior.

Stumbling upon such gems helps one to put things in perspective; that the little things we learned along the way, the performances we watched on street corners and in small makeshift baffas, remain a lasting impression.

There

is undoubtedly more to Sierra Leone’s contribution to African literature than

we can ever imagine.[There was] Thomas Decker’s JULIOHS SIZA, a Krio translation of William Shakespeare’s JULIUS CEASAR, BAD MAN BETE PAS EMTI OS by Esther Taylor-Pearce, GOD PAS KONSIBUL by Lawrence Quaku Woode, and PETIKOT KOHNA by Dele Charley.

But the big enchilada, the surprise of all surprises, was a book titled THEATER IN SIERRA LEONE: FIVE POPULAR PLAYS, edited by Iyunolu Osagie. The collection included the masterpiece BLOOD OF A STRANGER by Dele Charley, a play that was performed at the FESTAC in Nigeria in 1977.

The other huge surprise was John Kolosa Kargbo’s LET ME DIE ALONE.

Kargbo, a playwright, was arguably, the best to come out of Sierra Leone’s theater world. As a kid, I watched Kolosa plays like POYOTONG WAHALA and EKUNDAYO. He was instrumental, challenging and very detailed. He was a fearless warrior.

Stumbling upon such gems helps one to put things in perspective; that the little things we learned along the way, the performances we watched on street corners and in small makeshift baffas, remain a lasting impression.

Comments

Post a Comment